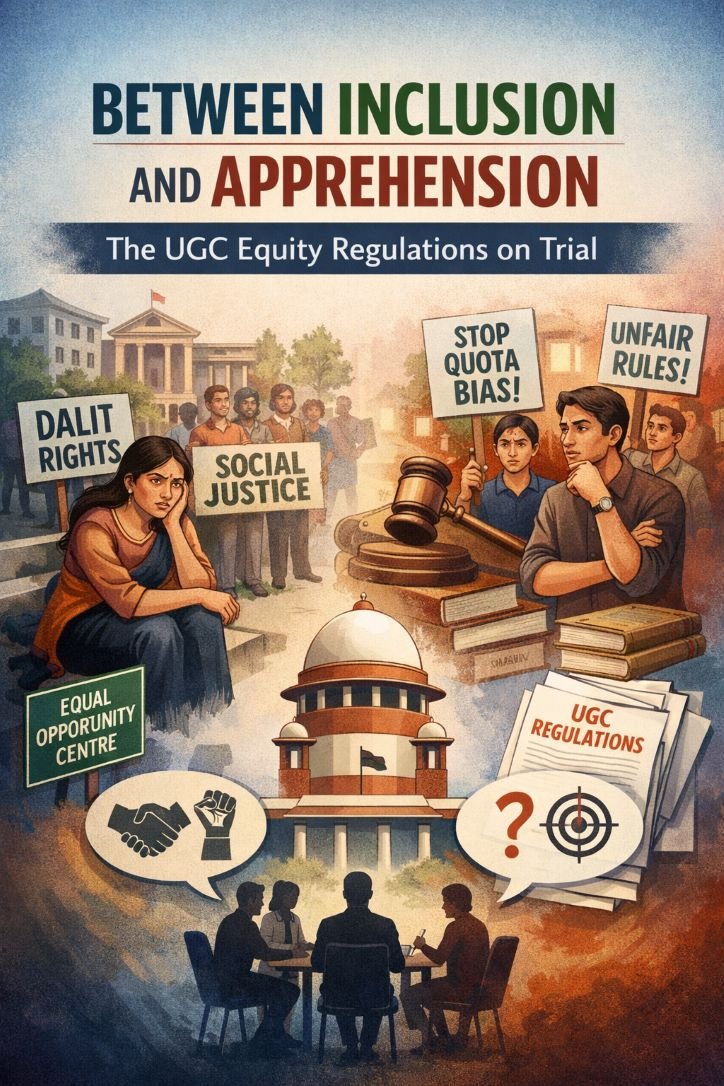

On the 130th birth anniversary of Bharat Ratna, Dr B R Ambedkar, the chief architect of the constitution and independent India’s first law minister, the worsening education scenario for marginalized, deprived and disadvantaged sections of society after covid19 pandemic, calls for a serious introspection on where it is headed

Even without Nelson Mandela reminding the world about the power of education for bringing about a change, like it or not truth is that education is both empowering as well as liberating since the dawn of civilization. And the journey continues as the world climbs evolutionary peaks. The demand for education is an aspiration grown from individual to communities and nations, and with consequences. And with time it has manifested in demand, rights, laws and a system of delivery and so on.

In India, for historical and other reasons, however, provision/demand for education has not attracted much attention or any marked centrality in well-known social movements in modern times and is still not part of a formidable political agenda. And that is strange?

According to Prof Gopal Pradhan, Director Equal Opportunity & faculty at School of Letters (SOL) , Ambedkar University Delhi, the movements have not thought about interfering in the system and the limited concern has been on reservations. “Traditionally it is a story of too much dependence on the state and politicians and education not being part of mass social movements,” he says while fearing that feudalism may be on a comeback way as the left ideological influence of post 1917 Russian revolution is on the wane throughout the world and the Covid19 pandemic has hastened it.

Long closure of schools also means end of gains in ending inequality, exclusion and social justice. “The very idea of a school as an imagination has collapsed,’ feels S. Srinivasa Rao is Associate Professor of Sociology of Education at Zakir Husain Centre for Educational Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). While drop outing was already a big challenge, the pandemic forced shutdown has larger implications for a vast population of first/second generation school goers. Malnutrition (because midday meals now not there), early marriages, child labor—all can take us back by decades and what will be its final picture nobody can tell at this stage.

According to Rao, the challenge about education can be understood if we look at the broad three phases of last two decades. The first phase will be post liberalization where access increased as infrastructure in terms of number of schools grew exponentially including rural areas at all levels—primary, upper primary, and secondary. All this was reflected in more than doubling of GER in higher education from about 8% in 2000 to 21% in 2013. Even GPI improved to the level that it became level. Improvements in teacher education, early education policy framework was part of this unfolding new evolution.

Access was clearly the policy prescription, enrollments increased and schools spread across. But it was not as if everything was as perfect. Even today single teacher schools in the country remain over more than 1.1 lakh and bulk of schools not compliant with RTE Act.

Talking of Right to Education and its enactment, it gave hope to all children in general but to families of downtrodden and poor in particular. It opened space and a role for civil society intervention and work. The phase 2 commenced with the NDA 2 coming to power in 2014 which pursed liberalization and conservative cultural thrust at the same time resulting in diluting the gains of the first phase. The government didn’t favor the Right to Education law and did best it ignore it even in the new National Education Policy.

The government also came in confrontation with the student movements which had begun to talk about issues outside traditional boundary of academics debates. The urban space that youth of marginalized groups occupied due to past affirmative action and reservations was increasingly seen as a threat to be crushed instead of taken as a part of natural churning in evolution of aspirational societies.

The phase 3 arrived with the pandemic, which forced closure of education institutions and therefore made access and completion of education for a large population on the other side of digital divide, lot more difficult and even beyond their reach. And, it has inadvertently handed over the education to the market dynamics as online or digital education came to rule the roost.

As the aspirations of people grow around education, commercialization of education and corporatization of institutions, is only natural and there are instruments that have been attempted throughout the world to justify it. From fee controls to coupons and now online education, regulating privatization of education looks beyond the capacity of the state. While it first protected the rights and thought it is its constitutional duty, now when the state itself has to give those were rights to its citizens and make provisions, it is looking the other way round. Dr Akash Bhattacharya of Azim Premji University feels the role of private sector needs to be clearly defined as most people are interconnected and can’t take us versus them position. The new realities need to be reflected in framing a pragmatic approach.

All this calls for a deep reflection and a debate on where all this should converge. Post-covid, country is already receding in its social development index , danger is it can give way to unbundling of gains in the universalization of education. A true tribute to Ambedkar would be taking a look at the situation the way he would have.

(The quotes used in the story are from a webinar on Inclusive and Equitable Education in India : Challanges before Dalits and Marginalised hosted by RTE Forum on April 13)