By Autar Nehru

On January 5, 2023, India, moved closer to allowing Foreign Higher Education Institutions (FHEIs) set up their campuses on Indian soil after the University Grants Commission (Setting up and Operation of Campuses of Foreign Higher Educational Institutions in India) Regulations, 2023 draft was released by the Government. While the final regulations are pending a last-minute deliberation apparently to look into the public feedback and suggestions received till January 18 (last date as per UGC notification), the intent seemingly was also to gauge the reactions and criticism to such a move, which has traditionally met stiff political opposition in the past. Ironically, the ruling BJP was among those who vociferously protested against the entry of foreign universities before 2014.

The history of allowing foreign universities entry into India has come a full circle. The first bill to this effect was introduced in 1995 in Rajya Sabha and then aborted only to be revived in 2007 as Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry, Operation, Maintenance of Quality and Prevention of Commercialization) Bill 2007. However, it couldn’t move beyond cabinet to the parliament because of the strong opposition from the left parties which were supporting UPA Government of that time. Another Foreign Educational Institutions (Regulation of Entry and Operations) Bill, 2010 was presented to Parliament in 2010, but was vehemently opposed by the right-wing BJP which made common cause with left-wing communists and was referred to Parliamentary Standing Committee, Finally the bill was introduced on January 13, 2013 by the then HRD minister Kapil Sibal but the long disruption of Parliament by the opposition killed it as the term of the Lok Sabha lapsed. Therefore, this time round instead of enacting legislation which could be torpedoed in Parliament, the Government has invoked clauses (f) and (g) of sub-section (1) of section 26 and clause (j) of section 12 of the University Grants Commission Act, 1956.

So, what has led to the change of heart on part of the ruling party? As a direct consequence of globalization and economic reforms, various reputed universities in the past three decades have set up over 300 campuses in other countries mainly in China, UAE, Singapore, Malaysia, and Qatar. Though most of these branches aren’t breaking into top rankings but Malaysia and Singapore have been able to emerge as reputed exporters of education and international education destinations. India where the GER as per the latest AISHE is 27.3% has also the distinction of being the second-largest student export market in the world after China. The argument put forth by UGC chairman, Prof M Jagadesh Kumar on a number of media platforms is that the need of Indian students is so big that the current and projected expansion may not be sufficient to meet the demand as also the NEP 2020 target of achieving 50% GER by 2035 is there. So, bringing in foreign universities will increase choice for students and foster a healthy competition with the domestic providers, which will raise the quality standards of higher education in India. He is also making it clear that through these regulations, the country is not seeking to stop those who are going aboard for studies (last year 4.5 lakh Indian students went aboard for study) but choice by having more comparable HEIs.

“The Foreign Universities draft norms are part of a long-term negotiation with the education sector as part of an attempt to change the direction of foreign exchange flows to the country. This set of norms provide further concessions to foreign universities as part of the journey, but it is unlikely to have any major direct impact straight away. In itself it stands as a letter of intent and invitation to good universities to increase engagement with Indian students within the country,” feels Meeta Sengupta, a former education consultant and a TV panelist on education matters.

According to sources, there was a lot of backroom discussion and negotiations with foreign governments and representatives of foreign HEIs at various levels to understand each other’s views and convergence on deliverables and creating an environment. UGC chairman, Prof Kumar in May 2022 had undertaken a series of discussion with several embassies and missions in Delhi. So, the intent for success of this move is very much there.

As per the draft regulations, two categories of FHEIs will be allowed—one: those figuring in the list of top 500 international rankings of a reputed ranking publisher and two, FEIs that are reputed in their home countries. Applicants will get two years to set up their campus and the initial approval will be for 10 years. Also, on the controversial issue of profit repatriation, the regulations without spelling it out explicitly say cross border funds flow will be determined by the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) 1999 and its Rules. Distance and online modes aren’t on table.

UGC, which will charge an annual fee from applicants and is empowered to inspect them, will govern the application process through a Standing Committee. This Committee shall assess each application on merits, including the credibility of the educational institutions, the programmes to be offered, their potential to strengthen educational opportunities in India, and the proposed academic infrastructure, and make recommendations thereof. Those passing the grade will get the initial approval within 45 days.

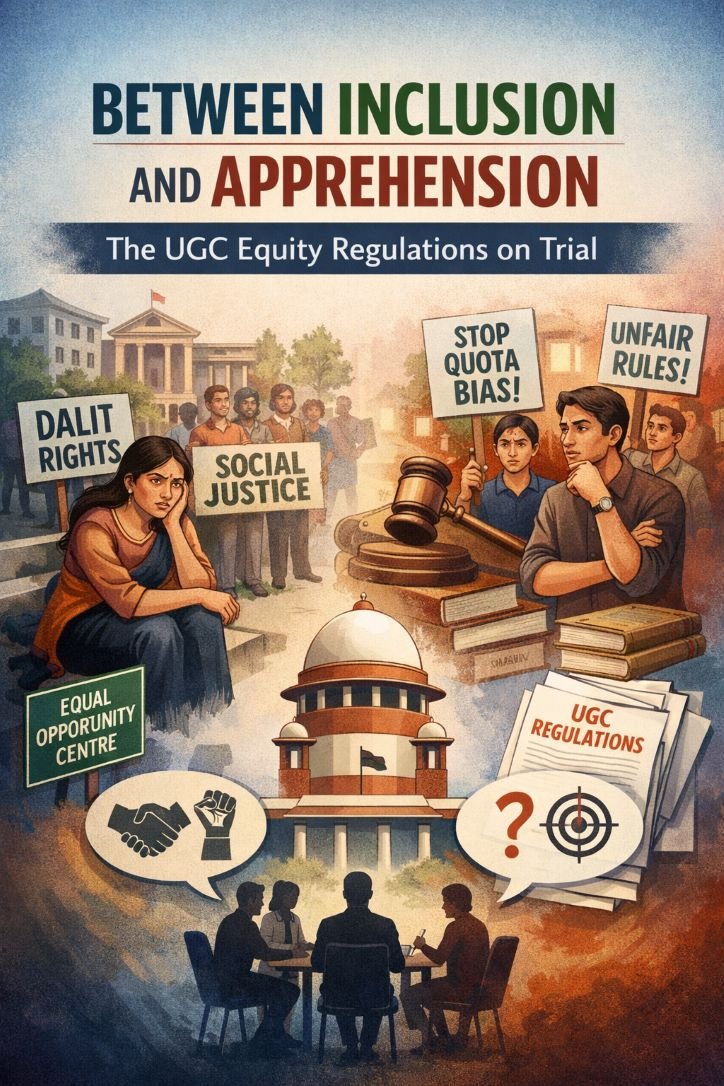

Being such a politically sensitive move, the entry of FHEIs through these regulations than a parliamentary legislation, is being opposed by left and other teacher and student associations. “This is the reactivation of ‘drain theory’, by which these educational East India Companies will try to plunder the vast education sector. The social justice concerns have been totally ignored which is very important in our context where higher education is a very effective means for social change,” said a statement from Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) affiliated teachers’ organisation, AADTA. “The idea of foreign university campuses in the nooks and corners of India might feel very empowering but the reality is that this will definitely weaken the Indian education system. The creation of such campuses won’t be of any benefit for the common Indian students and will only result in the creation of elite educational spaces which gatekeeps the knowledge between certain sections of the society,” SFI said in a statement.

While a lot of people are enthused about the prospect of foreign universities opening in the country, some experts point out that the Draft Regulations look at it as a licensing exercise while ignoring that higher education is a complex intellectual apparatus requiring an enabling ecosystem. ““As the first step, the government could strengthen NEP 2020 recommendations regarding “internationalisation-at-home” by empowering HEIs to bring in more foreign students. Enabling foreign universities and their research centres to build deeper and more meaningful collaborations with HEIs is also necessary. Ideally, the starting point should be to set up campuses as joint ventures in collaboration with top-ranked HEIs and enable faculty and student mobility. Such partnerships will also help build powerful synergies for the future”, wrote Bhushan Patwardhan, a former Vice Chairman, UGC and Yugank Goyal, associate professor at FLAME University, Pune in a joint critique in the Indian Express on January 12.

While it now appears that India will finally allow FHEIs to set up branches in the country as the final regulations emerge in coming weeks, it must be recognized that even after that it will be several years before the actual impact will be felt on higher education in the country. But if all goes well as per plan, India will certainly witness the first few foreign university campuses in the next 3-5 years from now as establishing universities and campuses, courses, creating research facilities, hiring faculty, relocating international faculty, and other challenges is a time-consuming complex process. Nonetheless, after 27 years since the idea of allowing foreign universities was seeded by the liberalization thought process of 1991 and think tanks like National Knowledge Commission, perhaps time has arrived at its realization.