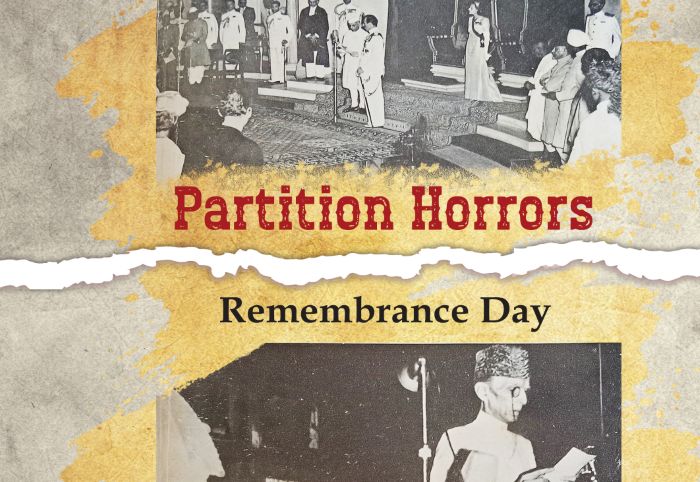

The NCERT’s new Partition modules—one for Classes 6–8 and another for Classes 9–12—released on Partition Horrors Remembrance Day (Vibhajan Vibhishika Smriti Diwas) this August 14, have ignited headlines and debate. By offering a more candid analysis of 1947, they mark a shift in how the tragedy of Partition is taught to schoolchildren.

Predictably, the modules have become a political flashpoint. The BJP-led government, often accused by critics of reshaping textbooks with nationalist overtones, is once again under scrutiny. The Congress has objected strongly, calling the account misleading and incomplete, particularly for omitting the role of right-wing Hindu organizations. The modules rest on a clear plank: Partition was not inevitable, and its responsibility lay with three principal actors—Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who demanded it; the Indian National Congress, which accepted it; and Lord Mountbatten, who hurried its implementation.

But beyond the political sparring, the real question is this: Should young students be taught the Partition story in such depth? Is it necessary to revisit such memories in classrooms, or does it serve as an essential lesson for 21st-century learners?

The answer lies in what education aspires to achieve. Partition was not merely a footnote to independence—it was the defining rupture that shaped South Asia’s political and economic trajectory. To understand India’s democracy, federalism, communal tensions, and even its foreign policy, students must grasp the magnitude of 1947. Far from burdening young minds with sorrow, this kind of history builds critical faculties—the famous “Cs” of education: critical thinking, creativity, communication, and collaboration.

Yes, in the 1950s and 1960s, the silence around Partition in school curricula was deliberate. India was fragile, still reeling from the trauma of nearly 1.5 crore displaced people, bloody riots, and a nation-building project that demanded unity above all. The leadership feared that keeping Partition memories alive might deepen wounds and breed discord.

Seventy-eight years later, those fears no longer hold. Today, Partition memory lacks the capacity to spark mass violence at a societal level. Politicians may weaponize it for rhetoric, but for ordinary citizens, an accurate and unflinching account of the tragedy only strengthens understanding and resilience. In fact, teaching Partition candidly is a way to counter new-age propaganda, radicalization, and selective amnesia about the costs of communal politics.

Across the Radcliffe Line, too, memory is fading. When official posters of Independence Day in Pakistan omit Jinnah’s portrait, it shows a society drifting from its roots. India, by contrast, gains by confronting its past honestly. Only by doing so can younger generations learn how historical wrongs unravel nations, and how difficult but necessary compromises must be made to preserve peace.

The NCERT modules, whatever their political genesis, deserve to be seen not as a revival of old wounds but as an act of remembrance and reckoning. The Partition of 1947 was one of the darkest chapters of modern history. Placing it squarely before students is not a burden—it is a duty.