The core responsibility of higher education institutions lies in what may be described as reverse engineering society—the deliberate and systematic effort to dismantle, reconfigure, and correct the inequities they inevitably mirror. This involves actively designing institutional cultures and systems that promote community, fraternity, and shared belonging across lines of class, caste, gender, religion, language, and region. Through common spaces, mixed housing, interdisciplinary classrooms, collaborative learning, and structured social interaction, universities can disrupt the patterns of segregation and social closure that dominate the external world.

While the inheritance of social fault lines is sociologically inevitable, the obligation to repair, transcend, and redesign them is the defining ethical mandate of higher education. In this sense, universities are not merely extensions of society; they are among its most powerful instruments of conscious self-correction.

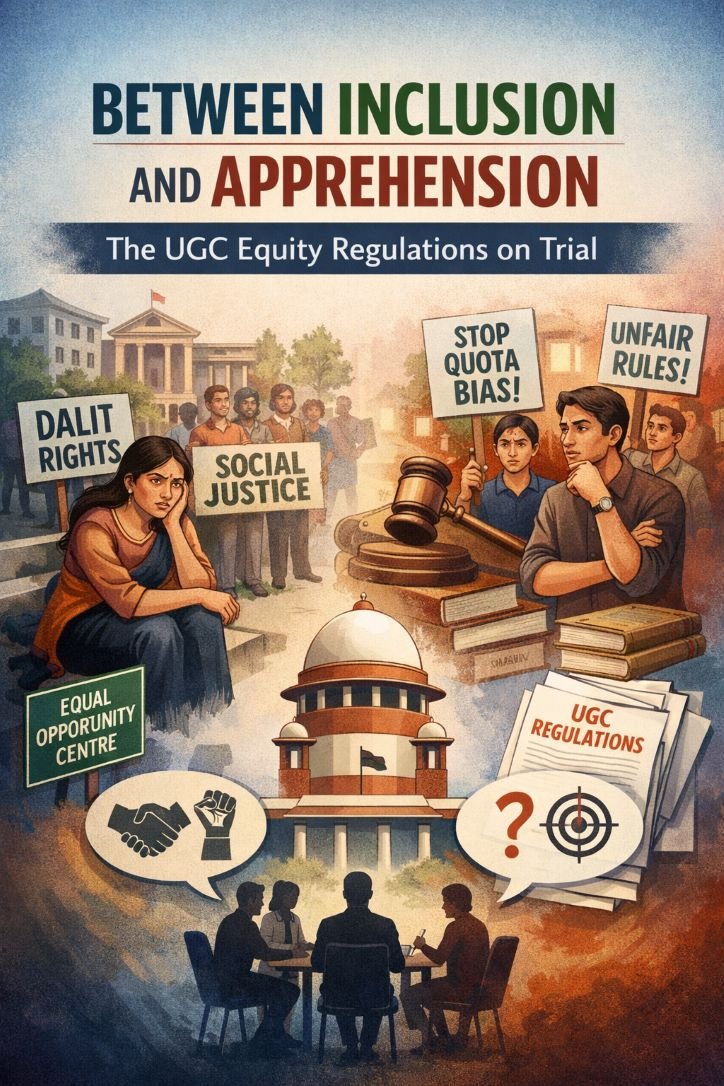

Seen against this backdrop, the Supreme Court of India’s decision to put in abeyance the University Grants Commission (Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions) Regulations, 2026—notified on January 13 and stayed within a fortnight on January 29—has been widely welcomed. The UGC Equity Regulations, 2026, intended to replace the 2012 framework, were perceived by many as poorly drafted and, as has now emerged, significantly altered at the bureaucratic level. Both the language and these post-draft tweaks carried the potential for misuse.

Viewed in the light of past experiences—particularly the perceived weaponisation of legal instruments such as the SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989—the new regulations triggered anxieties among sections of unreserved students about the possibility of false or frivolous complaints. The absence of adequate safeguards against misuse amplified these fears, which were further inflamed by social media influencers and political commentary. What began as regulatory reform soon acquired the tone of a broader social confrontation, evoking memories of the Mandal-era unrest of the early 1990s.

Faced with multiple petitions, the Supreme Court intervened decisively. It not only stayed the 2026 Regulations and restored the 2012 framework to avoid a regulatory vacuum, but also initiated a process of stakeholder consultation to address the ambiguities, inadequacies, and contentious provisions that rendered the new rules both unpalatable and potentially divisive.

To understand the origins of this regulatory shift, one must return to the limitations of the 2012 framework. As noted by Drishti IAS, the 2012 Regulations were largely advisory in nature: they mandated the creation of cells and officers, but lacked enforcement mechanisms, penalties for non-compliance, or meaningful oversight. In practice, most institutions treated these provisions as procedural formalities rather than substantive obligations. Dalit and student activists have long argued that without binding accountability, anti-discrimination measures remained largely symbolic, diluting their real-world impact.

The immediate push for the 2026 Regulations, however, came from the tragic cases of Rohith Vemula and Dr Payal Tadvi, both of whom died by suicide allegedly due to caste-based discrimination. Rohith Vemula, a PhD scholar at the University of Hyderabad, died on January 17, 2016. Dr Payal Tadvi, a resident doctor, was found dead in her hostel room at BYL Nair Hospital, Mumbai, on May 22, 2019. Their mothers filed a joint petition in 2019—W.P. (Civil) No. 1149/2019 (Abeda Salim Tadvi and Radhika Vemula vs Union of India, UGC and NAAC)—which is still under consideration by the Supreme Court. It was during the course of these proceedings that the Court directed the UGC to revise the existing regulations to address their perceived ineffectiveness.

According to Bhim Kumar, Member Delhi State Committee, Krantikari Yuva Sangathan (KYS), discrimination in the Indian HEIs is a stark reality. As per the data provided by the UGC to the Parliament Standing Committee on Education in 2025, complaints of caste-based discrimination increased from 173 in 2019-20 to 378 in 2023-24. This data was based on details collected from 2,256 HEIs across the country. “This data clearly demonstrates that caste-based discrimination is a living reality for students coming from marginalised communities. However, it needs to be pointed out that reports of such incidents are very minimal, as there was no proper mechanism to deal with caste-based discrimination. The UGC data states that of 3,522 HEIs, only 3,067 had established Equal Opportunity Cells as recommended by the UGC Equity Regulations 2012 which were largely advisory in nature. Moreover, not just discrimination based on caste, but on other grounds such as are a stark reality in HEIs. The UGC Regulations 2026, therefore, were addressing these various forms of discrimination, not just those based on caste,” he added.

At the same time, there was broad consensus that the regulatory framework needed updating to reflect the realities of a vastly expanded higher education sector. The 2026 Regulations therefore mandated that every higher education institution establish Equal Opportunity Centres (EOCs), along with Equity Committees, and appoint Equity Officers or Ombudspersons.

The new regulations provided for multiple channels for reporting complaints, including online portals, email, written submissions, and designated helplines. The regulations also introduced timelines for grievance redressal, requiring Equity Committees to convene promptly—often within 24 hours—and conclude inquiries within prescribed periods, with reports shared with both the head of the institution and the complainant. Institutions were further asked to set up 24×7 helplines, equity squads, and equity ambassadors to monitor compliance and serve as contact points for stakeholders.

Comparing 2012 with 2026

The new Equity Regulations, inspired by the National Education Policy 2020’s commitment to “full equity and inclusion”, define discrimination on grounds of religion, race, gender, place of birth, caste, or disability, particularly against Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, socially and educationally backward classes, economically weaker sections, and persons with disabilities. However, Section 3(c) narrows caste-based discrimination to only SCs, STs and OBCs.

The Regulations mandate every Higher Education Institution (HEI) to establish an Equal Opportunity Centre (EOC) with a faculty coordinator and an Equity Committee constituted by the Head of the Institution. The EOC is responsible for implementing equity policies, providing academic, financial and social counselling, enhancing campus diversity, and coordinating with external support agencies such as District and State Legal Services Authorities.

HEIs must also constitute Equity Squads to prevent discrimination, appoint an Equity Ambassador, and operate a 24×7 Equity Helpline. Complaints may be submitted through an online portal, the helpline, or in writing to the EOC coordinator, with an option for anonymity.

Non-compliance attracts penalties ranging from debarment from UGC schemes and academic programmes (including ODL and online modes) to removal from the UGC-recognised list under Sections 2(f) and 12B of the UGC Act, 1956, along with other punitive actions as decided by the Commission.

The new Equity Regulations, 2026 differ from the 2012 regulations in being both more comprehensive and more punitive. While the 2012 framework was limited to preventing discrimination in higher education and confined largely to SC and ST students, the 2026 regulations promote equity, dignity and safety, and extend coverage to OBCs, gender minorities and persons with disabilities. They also expand the scope beyond students to include teaching and non-teaching staff as well as online and distance learners.

Further, the complaint mechanism has shifted from a single Anti-Discrimination Officer and Equal Opportunity Cell to a multi-member Equity Committee and a strengthened Equal Opportunity Centre. Finally, institutional penalties, which were largely advisory in 2012, are now explicit, well-defined and enforceable.

So where did the framework go wrong?

The controversy deepened when Digvijaya Singh, Congress MP and Chairperson of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education, Women, Children, Youth and Sports, revealed that significant changes had been made to the draft regulations after the committee submitted its recommendations. In a detailed public statement, he clarified that two of the committee’s five key recommendations were ignored by the UGC. Most notably, the final version removed a draft provision that penalised students for filing false complaints of discrimination—a decision taken unilaterally by the UGC and not suggested by the committee.

He further noted that general category students were not explicitly included among groups vulnerable to discrimination, leading to the perception that the regulations implicitly assumed that only reserved category students could be victims and only general category students could be perpetrators. This omission, too, was not a recommendation of the parliamentary committee.

Experts have largely welcomed the Supreme Court’s intervention while blaming the crisis on poor regulatory drafting. As Prof. Raj Kachroo, founder of Aman Trust and a member of the National Taskforce on Mental Health, observed:

“Nobody is denying the need for a framework to address discrimination in educational institutions, but these poorly drafted regulations created a situation of valid apprehensions. In haste, or without applying their minds, the bureaucracy overlooked the fact that discrimination needs to be clearly defined and backed by proper implementation and monitoring mechanisms. It is ridiculous to see all this reduced to a spectacle. Imagine 60,000 helplines corresponding to the number of HEIs and equity squads—where do these fit in? They blindly copied the anti-ragging apparatus without considering that student-to-student discrimination is already covered by the Anti-Ragging Regulations of 2016 and is working reasonably well. Ragging involves group harassment in hostels, classrooms, canteens, and other public spaces, which justified squads. Discrimination, however, is often subtle, indirect, and occurs in private interactions, assignments, and evaluations. Institutional discrimination against students and staff needed clearer emphasis. Prevention, not punishment, should be the objective, and strong components of awareness are missing.”

Three broad conclusions emerge. First, there is near-universal agreement that a robust equity framework is necessary, but it must not be politicised or weaponised in ways that deepen social polarisation. Second, the regulatory mechanism requires far greater conceptual clarity, institutional realism, and administrative foresight. Third, the emphasis must shift from reactive punishment to preventive culture-building—strengthening student services, fostering inclusion, and treating discrimination as a structural problem requiring systemic solutions.

The Supreme Court has now opened the space for a more reasoned, participatory, and evidence-based debate. With the next hearing scheduled for March 19, the challenge is to move beyond ideological confrontation and craft a framework that is legally sound, socially just, administratively workable, and ethically credible—for every student who enters India’s campuses. -AN