As Bihar prepares to vote for the forthcoming fiercely contested election on 6th and 11th of November, one theme unites both sides of the political divide: the aspirations of its youth. With nearly 60% of the state’s population under the age of 35, it is hardly surprising that jobs, education, and youth empowerment dominate every manifesto and campaign speech. Yet, as always in Bihar, the real question is not the intent — but the feasibility and implementation.

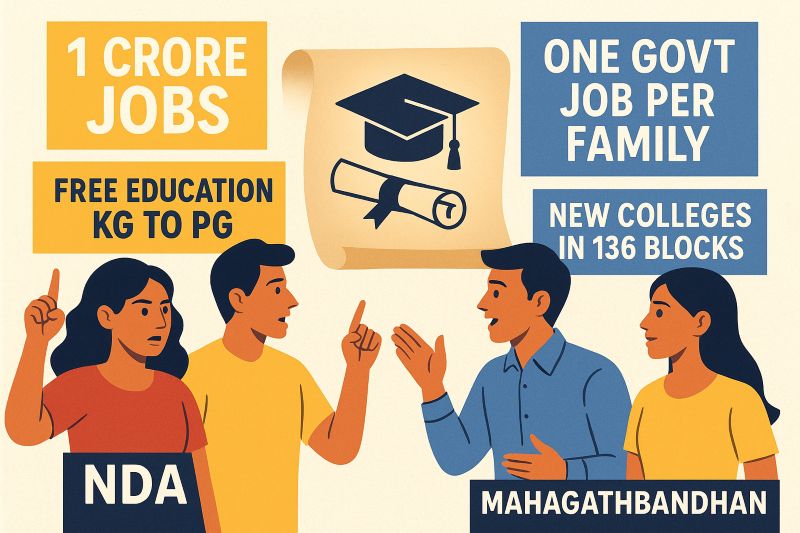

The ruling National Democratic Alliance (NDA) has staked its campaign on the promise of creating one crore jobs — a sweeping figure meant to signal ambition and scale. The party also promises free education from kindergarten to post-graduation for poor, the establishment of Mega Skill Centres in every district, and a skill census to align education with employability.

The NDA’s narrative is clear: long-term structural reform. It seeks to transform Bihar into a “global skilling hub” where young people are trained, certified, and ready for the job market. Skill development, industrial partnerships, and educational continuity are cast as the engines of growth.

On the other side, the Mahagathbandhan or INDIA bloc led by the RJD has chosen a dramatically different message — one rooted in immediacy and entitlement. Its flagship promise, “One government job per family,” has captured public imagination with its simplicity. Accompanying pledges include free travel for students to examination centers, waivers for exam fees, new degree colleges in 136 blocks, women’s colleges in every subdivision, and the regularisation of contractual and outsourced workers.

Where the NDA speaks of skilling and private sector partnerships, the opposition speaks of guarantees and government responsibility. Their manifesto channels the frustration of an underemployed generation that feels left behind by “training without placement” policies.

Promises and Pitfalls

Both visions appeal to different instincts among Bihar’s youth. The NDA’s emphasis on employability, skill mapping, and education continuity suggests a long-term investment in human capital. But the challenges are substantial: How will the state, with limited fiscal space, fund free education from KG to PG? Can a skill census meaningfully translate into jobs when Bihar’s industrial base remains weak and many trained workers migrate out of the state?

The Mahagathbandhan’s promises, meanwhile, resonate emotionally but raise serious fiscal and administrative questions. A “job guarantee” for every family, even if phased over years, would impose an enormous burden on Bihar’s already stretched finances. Creating hundreds of new colleges will require infrastructure, qualified faculty, and years of planning. Regularising all contractual workers may win votes, but could strain the state’s wage bill and limit its ability to invest in new employment schemes.

The Politics of Youth and Expectation

In truth, both sides are responding to the same underlying crisis — youth disillusionment. For years, Bihar’s young population has been caught between exam paper leaks, delayed recruitment drives, and outmigration. Families spend heavily on coaching and travel to distant cities in search of opportunity. The Mahagathbandhan’s manifesto seeks to soothe this anger with immediate relief; the NDA’s seeks to redirect it through capacity-building and structural reform.

But while the tone differs, both manifestos share one strength: they acknowledge that education and employment are inseparable. The political consensus that youth empowerment is the state’s central issue is a positive shift from older identity-driven campaigns.

Beyond Election Season

What Bihar’s youth now need are not grand promises, but credible roadmaps. For the NDA, that means translating slogans like “1 crore jobs” into verifiable programs — with transparent targets, district-level placement data, and measurable outcomes from skill centres. For the Mahagathbandhan, it means backing its moral appeal of “one job per family” with detailed costing, recruitment reform, and clear delivery timelines.

The state’s political class must also acknowledge that migration will not stop unless Bihar creates value chains at home — through local entrepreneurship, agro-industries, digital hubs, and public-private partnerships in education and skills. Otherwise, even the best-trained youth will continue to leave in search of better prospects.